Introduction

Long before the Hebrew prophets walked the hills of Canaan, the lands of the Levant were alive with myriad gods, spirits, and sacred rites. The rise of Judaism brought monotheism and strict devotion to Yahweh, yet within the texts, rituals, and cultural memory, traces of older beliefs linger. These echoes remind us that religions do not emerge in isolation — they grow from the soil of preceding traditions, reshaping ancient customs into new forms.

Pagan Roots and Transformations

The Israelites lived among cultures rich in polytheism: Canaanites, Babylonians, Egyptians, and Mesopotamians, all of whom venerated multiple deities and natural spirits. Many early Hebrew practices and narratives show signs of adaptation, reinterpretation, or contestation of these older traditions.

- Sacred Spaces: Before the Temple in Jerusalem, the Israelites used high places, groves, and altars — often sites previously dedicated to Canaanite gods. Many biblical texts warn against idolatry at these locations, suggesting a conscious effort to redirect older sacred practices toward Yahweh.

- Festivals and Agricultural Cycles: Jewish holidays often align with seasonal cycles that predate monotheism. Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot correspond to spring lambing, harvest, and fruit-gathering festivals of the ancient Near East. Rituals such as dwelling in sukkot (temporary booths) or offering first fruits reflect agricultural rites that were once tied to multiple deities but were absorbed into worship of Yahweh.

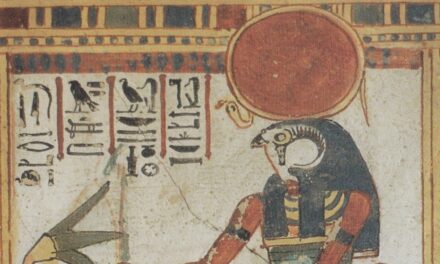

- Angels, Spirits, and Folk Beliefs: Concepts of angels, demons, and protective spirits in Judaism echo older Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Canaanite beliefs. Some scholars trace the archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael to earlier divine intermediaries, transformed to serve a monotheistic framework.

- Ritual Objects and Practices: Symbols like the menorah, incense, and ceremonial washing carry echoes of temple rituals in neighboring pagan cultures. Even dietary laws may have roots in ancient symbolic purity practices shared across the region.

Modern Reflection

Today, Judaism preserves these ancient traces in its calendar, rituals, and sacred narratives. The rhythm of festivals tied to harvest and fertility, the emphasis on sacred space and ritual purity, and stories that preserve motifs from older mythologies all hint at the deep interplay between the old and the new.

Even when consciously forbidden, older practices shaped the structure and imagination of Jewish ritual life. The Torah’s injunctions against idolatry, for example, presuppose the presence of persistent pagan practices in daily life. Synagogues, holidays, and liturgy thus carry layers of history — a fusion of memory, adaptation, and reorientation toward monotheism.

Conclusion

Paganism in the ancient Levant may have receded, but its echoes survive in the sacred calendar, rituals, and symbols of Judaism. The worship of Yahweh, though absolute, carries within it the shadow of earlier gods and traditions — a reminder that faith evolves, often in conversation with the past. And so we might ask: when lighting the menorah, celebrating the harvest festivals, or walking in the paths of ancient temples, are we honoring only Yahweh, or also tracing the faint footsteps of the gods who came before?