Introduction

In the vast deserts of Arabia, where sand meets sky and the wind carries the whispers of ancient caravans, Islam emerged as a transformative faith. Yet even within this strict monotheism, echoes of earlier beliefs linger — reminders that spiritual traditions rarely exist in isolation. Long before the Prophet Muhammad’s revelations, the Arabian Peninsula was home to tribal deities, sacred stones, and rituals tied to the cycles of nature. Some of these practices, subtly woven into Islamic culture, reveal how old traditions can persist, transform, and endure beneath the surface of a new faith.

Pagan Roots and Transformations

Pre-Islamic Arabia was a mosaic of polytheism and animism. Tribes worshiped a pantheon of gods, spirits, and sacred objects:

- Hubal, the chief deity of the Kaaba, represented divine authority and justice.

- Al-Lat, Al-Uzza, and Manat were powerful goddesses linked to fertility, fate, and protection.

- Sacred stones, wells, and trees were venerated as vessels of spiritual power.

When Islam emerged, it introduced strict monotheism — the worship of Allah alone — but it also absorbed and transformed pre-existing sacred structures and practices to ease the transition for Arabian peoples.

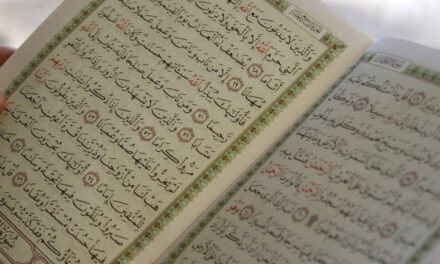

- The Kaaba: Islam preserved the Kaaba in Mecca as the center of worship, transforming a site previously used to house idols into a shrine devoted to the one God. The rituals of circumambulation (Tawaf) around the Kaaba echo earlier practices of walking around sacred stones or temples in honor of the gods.

- Hajj Pilgrimage Rituals: Many elements of the Hajj ritual reflect pre-Islamic customs. The symbolic stoning of the pillars (Jamarat) recalls earlier rites meant to ward off evil spirits. Drinking from the Zamzam well, linked to the story of Hagar and Ishmael, was also sacred in pre-Islamic times.

- Festivals and Timing: Islamic festivals such as Eid al-Adha coincide with seasonal cycles and historical pilgrimage practices that were already central to Arabian religious life. The themes of sacrifice, renewal, and communal gathering echo older pagan traditions of offering and thanksgiving.

- Spiritual Beings and Folk Practices: Belief in jinn, spirits inhabiting natural elements, pre-dates Islam but continues as part of Islamic cosmology. Similarly, many folk practices — such as blessing homes, tying amulets, or protective prayers — reflect older customs adapted into an Islamic framework.

Modern Reflection

Today, these traces remind us that Islam, like all religions, exists on a continuum of cultural memory. While its theology is monotheistic and distinct, its rituals, sacred spaces, and folk practices bear subtle testimony to Arabia’s spiritual past. Pilgrims circle the Kaaba, echoing ancient practices of devotion; seasonal festivals celebrate sacrifice and renewal in ways that resonate far beyond doctrinal origin; and local customs — from talismans to prayers at sacred wells — preserve memories of a world that existed before Islam crystallized in the 7th century.

Recognizing these layers deepens our understanding of faith as a living, adaptive tradition. It also illustrates a universal truth: human devotion is rarely born anew — it grows atop the roots of what came before.

Conclusion

Paganism in Arabia may have faded, yet its influence endures quietly, woven into ritual, sacred space, and the imagination of the faithful. The desert gods may no longer be called by name, but their echoes persist in the practices and sacred rhythms of Islam. And so we must ask: when pilgrims circle the Kaaba, or seek protection through prayer and sacred objects, are they honoring only Allah, or are they also walking in the shadows of the gods that once ruled the sands?